The affordable housing crisis in the United States has plagued Americans across the country since the Great Recession—and is only getting worse. 2022 estimates indicate that the U.S. needs some four to five million more homes on the market than it has right now. Housing costs have become increasingly untenable for renters and buyers alike; over 40% of renters are cost-burdened (meaning they spend more than 30% of their income on housing costs), and housing prices are rising faster than wage growth in 80% of U.S. markets. Moreover, the situation has been exacerbated by the work-from-home boom and supply chain shortages that resulted from the COVID-19 pandemic. Demand increased as Americans moved to the suburbs; at the same time, supply decreased due to shortages of labor and building materials.

We talk to Andra Ghent, Professor of Finance at the University of Utah’s David Eccles School of Business, to discuss the problem of housing affordability, as well as what solutions might be possible for the public and private sectors.

How has the work-from-home boom changed housing affordability and migration patterns since the pandemic?

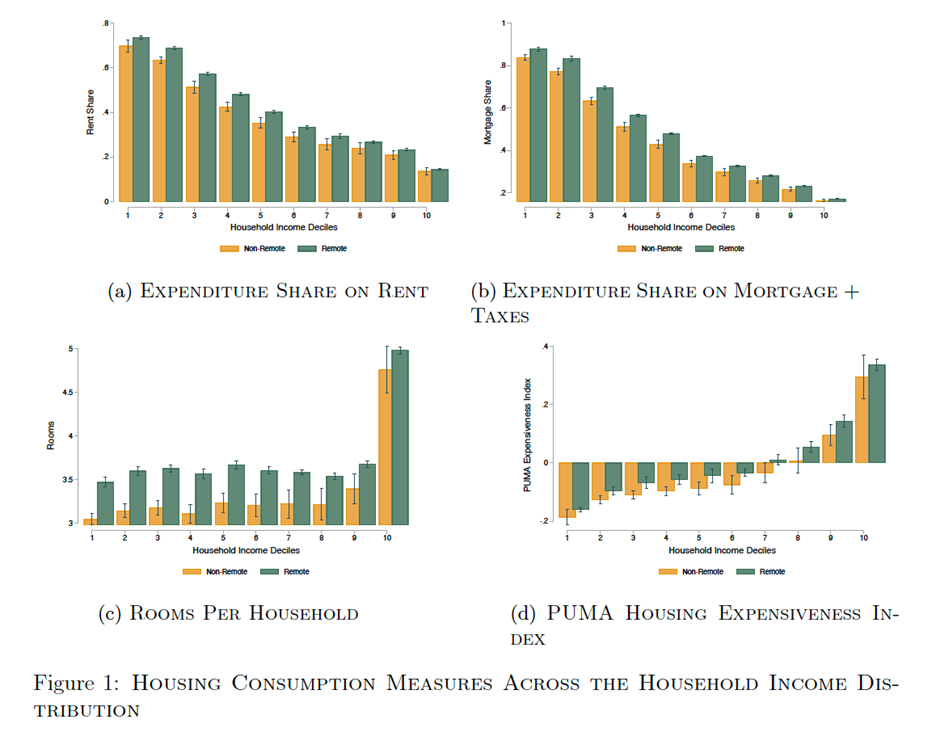

People need more space to be able to work remotely. We know this from pre-pandemic data showing that people who worked remotely spent a larger fraction of their income on housing and had more rooms in their homes (see graph below from Stanton and Tiwari, 2021). Importantly, it’s not just dedicated home office space that people want more of when they work remotely. They also use the other parts of their home more intensively (bathrooms, kitchens, basement gyms) since they’re more likely to do all the ancillary activities they did at the office at home now. The increase in work-from-home thus lead to a big increase in housing demand that increased housing prices.

Working from home makes living in the suburbs less costly since people only need to commute 2-3 days per week instead of 4-5. Subsequently, it shifted housing demand towards the suburbs, particularly in cities where people face long commutes, where suburban space is relatively cheap, and with high shares of white-collar workers.

In the long run, the increase in house prices will moderate a bit as home builders are able to add more space where people want to live. That said, municipalities have enacted increasingly onerous land use regulations that are making it harder for home builders to add supply—even in the long run—so some of the increase in home prices is permanent.

How are higher interest rates affecting renters as opposed to homeowners?

Unfortunately, any fall in home prices from the increase in interest rates is not due to either a short-run or long-run improvement in affordability for either renters or buyers. Home prices are just the capitalized value of the future expected stream of rents, and the rate at which they are being capitalized has risen. This is part of why you are seeing some moderation in home prices or even outright declines in some places. Mostly, the rise in rates means that some people who previously could have qualified for a mortgage can’t right now. As a result, there are fewer buyers bidding on any homes on the market.

The rise in interest rates also means that many would-be home sellers are effectively locked into their current home since they can’t take their current mortgage rate with them if they buy a new house. This means the market for existing homes is especially thin.

Rents are not falling significantly, so it would be a mistake to think that affordability has improved because of the increase in interest rates. Nothing has improved for renters; in fact, new construction of housing is declining because homebuilders are having a harder time getting deals to pencil with the increase in interest rates. That means that the rise in rates will decrease affordability in the medium term.

What solutions are most viable from the public and private sectors? Are there examples of successful policies that have increased the supply of affordable housing?

We need states to step in and preempt municipalities from enacting and enforcing land use restrictions that raise housing costs. Land use control is a police power that is constitutionally guaranteed to states, not cities. While states often delegate the power to municipalities, they can take it back when cities don’t use it for the public benefit. Because housing markets are regional, any individual city does not bear the full cost of making it hard to build.

The best chance we have to improve housing affordability in the long term is to reduce construction costs through automation of construction processes. There is a lot of innovation going on in housing construction – “modular” housing, 3D printing, and so forth – but right now there are problems getting these processes to scale and become affordable. We’ve seen little to no productivity growth in housing construction in 50 years, unlike what we’ve seen in the rest of the manufacturing sector because we haven’t seen scale in manufactured housing.

So, we need manufactured housing built at scale. To make this possible, we need harmonization of land use law to make it possible to build the same type of housing in many cities and know it adheres to the code. HUD can change its manufactured housing definition to allow home builders to remove the chassis and still have it count as manufactured housing. This needs to be accompanied by laws at the state level mandating that manufactured housing is a permitted housing type in any zoning code that allows single-family housing. Otherwise, manufactured housing will get relegated to parks.

Source: kenaninstitute.com ~ Image: keananinstitute.com